"It is not a question, here, of searching for an 'absolute' of beauty. The artist is neither painting history nor his soul. And it is because of this that he should neither be judged as a moralist nor as a literary man. He should be judged simply as a painter."

"So, after the literary schools that wanted to give us a distorted, superhuman, poetic, touching, charming, or proud vision of life, the realist or naturalist school came, which sought to show us the truth, nothing but the truth and the whole truth."

Guy de Maupassant"Realism aims at an exact, complete and honest reproduction of the social environment, of the age in which the author lives, because such studies are justified by reason, by the demands made by public interest and understanding, and because they are free from falsehood and deception. This reproduction should be as simple as possible so that all may understand it."

Edmond Duranty"[They] call me 'the socialist painter.' I accept that title with pleasure. I am not only a socialist but a democrat and a Republican as well - in a word, a partisan of all the revolution and above all a Realist. for 'Realist' means a sincere lover of the honest truth."

"Painting is the representation of visible forms. The essence of Realism is its negation of the ideal."

"One must be of one's time and paint what one sees.""It is the treating of the commonplace with the feeling of the sublime that gives to art its true power."

"The big artist keeps an eye on nature and steals her tools."Though never a coherent group, Realism is recognized as the first modern movement in art, which rejected traditional forms of art, literature, and social organization as outmoded in the wake of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. Beginning in France in the 1840s, Realism revolutionized painting, expanding conceptions of what constituted art. Working in a chaotic era marked by revolution and widespread social change, Realist painters replaced the idealistic images and literary conceits of traditional art with real-life events, giving the margins of society similar weight to grand history paintings and allegories. Their choice to bring everyday life into their canvases was an early manifestation of the avant-garde desire to merge art and life, and their rejection of pictorial techniques, like perspective, prefigured the many 20 th -century definitions and redefinitions of modernism.

Gustave Courbet said he painted his hometown's "mayor, who weighs 400, the parish priest, the justice of the peace, the cross bearer, the notary Marlet, the assistant mayor, my friends, my father, the choirboys, the grave digger, two old revolutionaries" to depict the funeral of his great-uncle in his Burial at Ornans (1849-51) - thus painting his reality. When exhibited the painting created such an uproar and launched Realism, that the artist said later, "Burial at Ornans was in reality the burial of Romanticism."

Beginnings and Development Concepts, Trends, & Related Topics Later Developments and Legacy

Even before Realism began as a coherent trend in the 1840s, Daumier's prints and caricatures engaged with the social injustices that would color the works of Courbet and others. Insurrection against the monarchy of Louis Philippe I reached a boiling point in April 1834, and a police officer was killed during a riot in a working-class neighborhood. In retaliation, government forces brutally massacred the residents of the building where the killer was believed to be hiding. In Rue Transnonain, Daumier revealed government excess with an emotionally provocative image showing the aftermath of the government's grossly disproportionate reaction, focused on the corpse of an unarmed civilian lying atop the body of his dead child. This topical, straight-from-the-headlines print denouncing the monarchy participates in Realism's assault on traditional power structures.

Lithograph on paper - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

With A Burial at Ornans, Courbet made his name synonymous with the young Realist movement. By depicting a simple rural funeral service in the town of his birth, Courbet accomplished several things. First, he made a painting of a mundane topic with unknown people (each attendee is given a personalized portrait) on a scale traditionally reserved for history painting. Second, he eschewed any spiritual value beyond the service; the painting, often compared to El Greco's Burial of Count Orgaz (1586), leaves out El Greco's depiction of Christ and the heavens. Third, Courbet's gritty depiction showed the fashionable Salon-goers of Paris their new political equals in the country, as the 1848 Revolution had established universal male suffrage. Artistically, Courbet legendarily stated, "A Burial at Ornans was in reality the burial of Romanticism," opening up a new visual style for an increasingly modern world.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

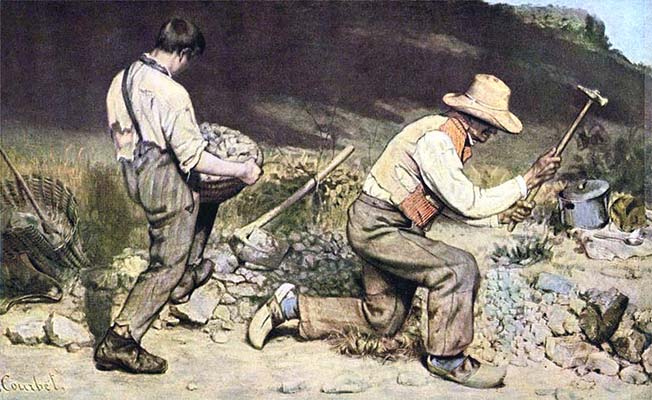

At the same Salon of 1850-51 where he made waves with A Burial at Ornans, Courbet also exhibited The Stone Breakers. In the painting, which shows two workers, one young, one old, Courbet presented both a Realist snapshot of everyday life and an allegory on the nature of poverty. While the image was inspired by a scene of two men creating gravel for roads, one of the least-paying, most backbreaking jobs imaginable, Courbet rendered his figures faceless as to make them anonymous stand-ins for the lowest orders of French society. More attention is given to their dirty, tattered work clothes, their strong, weathered hands, and their relationship to the land than to their recognizability. They are, however, monumental in size and shown with a quiet dignity befitting their willingness to do the unseen, unsung labor upon which modern life was built.

Oil on canvas - Destroyed by bombing in Dresden during World War II

Part of a "trilogy" of paintings celebrating France's rural denizens, The Gleaners serves as something of a feminine pendant to Courbet's The Stone Breakers (1849-50). Gleaning was perhaps the lowest form of work for women in French society, a practice wherein female peasants were allowed to comb the fields after the harvest, "gleaning" bits of grain that were left behind to take home for food; hours of hunched-over labor would often be rewarded with a small amount of meal. Millet certainly meant for the painting to call attention to the plight of the rural poor. Nevertheless, Millet's women are tied visually to the land, their bowed bodies glance the horizon, suggesting a quiet dignity and sense of belonging. Despite the calm warmth with which his subject is portrayed, Millet received intense criticism for The Gleaners from a wealthy art public to whom the painting spoke to contemporary concerns about the possibility of violent Socialist revolution by an exploited proletariat.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

After Courbet's succès de scandale at the Salon of 1850-51, Manet was the next major Realist artist to actively court controversy. Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, exhibited at the Salon des Refusés of 1863, did so with its rendering of a pair of well-dressed Parisian dandies entertaining two women - one naked, one semi-naked - at an outdoor picnic. Indeed, Le déjeuner was connected with prostitution in the Bois de Boulogne, a park where male middle-class city dwellers went with hired escorts. Beyond the social scandal created by this lascivious scene of mixed company, Manet's combination of a figural group borrowed from several Old Master works with the flattened snapshot aesthetic of Realism infuriated many art critics. Manet called attention to the false refinement of wealthy Parisian society, with nudes available in its museums and naked call girls in its forests, while creating a work that modernized classic painting. His distortion of perspective, a refusal to follow the Renaissance model of the canvas as a "window onto the world," laid the groundwork for the formal experimentation of Impressionism and later movements.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Though Whistler is considered among the Realist artists due to his direct style of painting and rejection of academic standards, he stands out as an outspoken advocate for "art for art's sake." Whistler declared openly that "art should be independent of all claptrap - should stand alone. and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism and the like." Rather than making social statements, he gave his works titles like Symphony in White, using musical terms to suggest harmonious arrangements within a dominant "key." This idea prefigured connections drawn between music and abstract art in the 20 th century by artists like Georges Braque and Wassily Kandinsky. Critics, however, still chose to read meaning into Symphony in White, claiming that the girl's disheveled hair and dropped bouquet represented a loss of innocence or virginity. For his part, Whistler resented the idea that his art carried hidden content outside of what was on the canvas.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

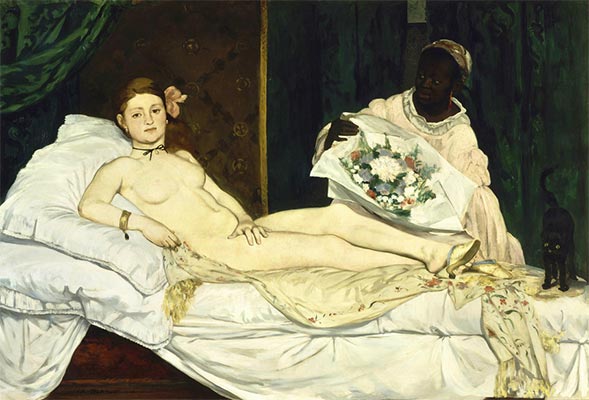

Manet capitalized on the publicity generated by his scandalous Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (1862-63) by exhibiting Olympia at the Salon of 1865. He modeled Olympia compositionally on Titian's Venus of Urbino (1538), which has been described alternately as either a wedding portrait of a young bride or a sort of "elite pornography": the depiction of a high-class courtesan. Given either interpretation, Manet's painting was quite clearly that of a prostitute, identified by the orchid in her hair and her various baubles, stark in its contrast between her flat, pale flesh and the dark background of her small room. The unapologetic, confrontational gaze with which she addresses the viewer (from above) was certainly meant by Manet to challenge French society's hypocritical notions of propriety, in an admittedly incendiary fashion.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

The political resonance of Realism had a powerful effect on art outside of France, as artists from across Europe and beyond used it to call attention to social inequality in their own countries. Ilya Repin became the most celebrated painter of his time in Russia for his sympathetic depictions of peasant traditions and low-class labor. Following Tsar Alexander II's 1861 reforms, which emancipated over 22 million serfs, Russian artists began to tailor art toward the edification of the lower classes. In Barge Haulers on the Volga, a team of poor, downtrodden workers pull a ship upstream. Yoked almost like farm animals, they are shown to be destitute and demoralized, but powerful, and Repin was critically praised for his depiction of the strength of the Russian spirit. The men center around a younger figure, who activates the painting by stepping out of line, indicating the possibility of heroic escape from lower-class toil. Repin thus achieved a very difficult balance: he pleased the Tsar while locating utopian potential in the exploited world of rural labor. Barge Haulers stands as a prefiguration of these very tensions that would explode in Russia in the early-20 th century.

Oil on canvas - State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

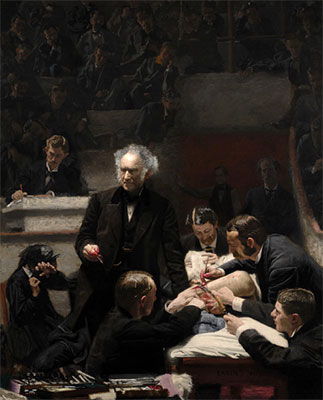

Eakins's eight-foot-tall portrait of the surgeon and professor Samuel Gross is a masterpiece of American Realism. Its direct portrayal of the blood and viscera of his patient's open body updated the false cleanliness and decorum of Rembrandt's The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632) with uncompromising realism. Submitted for the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, the painting was deemed too graphic to exhibit, though even its detractors conceded its vigor and power. Eakins, in many ways, was the fountainhead of Realism in the United States, coming as he did after the Romantic landscape tradition of the Hudson River School. The next-generation Realist painters of the Ashcan School were largely from Eakins's hometown of Philadelphia and were undoubtedly influenced by his strength of objectivity, observation, and representation.

Oil on canvas - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

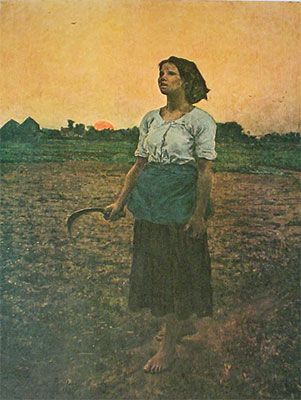

Artist: Jules Breton

One of the most famous works of French Realism, Jules Breton's Song of the Lark received broad acclaim as a less confrontational, more widely accepted version of Realist painting. Breton's late-century Realism carries a hint of poetic allegory, as the lark is traditionally a symbol for daybreak. His peasant woman stands in the middle of a field, holding a scythe, while the sun rises on the horizon. The soft colors of the sky create a beautiful backdrop for the strong-willed, barefoot farmworker. Breton's glorification of hard work made the painting extremely popular in his home country as an emblem of French fortitude and as one of pious hard work in the largely Protestant, Reconstruction-era United States. Indeed, his paintings of single peasant women in fields became so popular that Breton had prints made of many of them and occasionally produced painted copies.

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

Established in 1648 by Louis XIV, the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture or Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture governed the production of art in France for nearly two centuries. Given France's prominence in European culture during that time, the Academy set standards for art across the continent, providing studio training for young talent and recognizing artistic achievement at its semi-regular Salon exhibitions.

The "highest" form of art, established by the Academy in a 1668 conference, was history painting: the large-scale depiction of a narrative, typically drawn from classical mythology, the Bible, literature, or the annals of human achievement. Only the strongest painters were allowed to paint in this genre, and their works were the most celebrated by the Academy. Descending in importance in the hierarchy of genres were portraiture (the depiction of important persons), genre scenes (the depiction of peasants, or "unimportant" persons), landscape (the depiction of living nature), and still life (nature morte, or "dead nature").

Spurred by archaeological discoveries in Greece and Italy in the mid-18 th century and Enlightenment ideals of reason and order, Neoclassicism became the mode par excellence for history painting in the late 1700s. Neoclassical history painting, exemplified in the work of Jacques-Louis David, used classical references, compositional techniques, and settings to comment upon contemporary events. His famous Oath of the Horatii (1784), for example, communicated the civic value of patriotism in the guise of a story from the Roman historian Livy.

In response to Neoclassicism, the Industrial Revolution, and the Enlightenment's rationalization of life and society, Romanticism embraced irrational, intense emotion and exotic subject matter as more authentic sources for artistic creativity. Rather than beautifully ordered outdoor scenes, Romantic landscapes became arenas for the sublime conflict between man and nature. In place of David's praise of civic virtue were history paintings like Eugène Delacroix's Death of Sardanapalus (1827): a turbulent, chaotic scene inspired by a Lord Byron play wherein the titular king of Assyria commands his possessions destroyed and his terrified, beseeching wives massacred in the face of final military defeat.

While Romanticism might have rejected certain tenets of Neoclassicism, it did not drastically change the 17 th - and 18 th -century institutions of art and society. The near-perpetual state of revolution in France in the 19 th century provided an impetus to enact a more radical change. After the initial 1789 Revolution, France went through the First Republic, the First Empire under Napoleon Bonaparte, the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, the 1830 Revolution, the July Monarchy, the 1848 Revolution, the Second Republic, the Second Empire, the Franco-Prussian War and institution of the Paris Commune of 1871, and the establishment of the Third Republic.

Challenging Neoclassicism and Romanticism as escapist in the face of the larger societal issues brought by the turbulent 19 th century, Realism began in France in the 1840s as the cultural aspect of a larger response to ever-changing governance, military occupation and economic exploitation of the colonies, and industrialization and urbanization in the cities. Realism, more than the simple representation of nature, was an attempt to situate oneself in the "real": in scientific, moral, and political certainty.

In the 1830s, this push toward scientific positivism manifested itself in the advent of photography. Louis Daguerre publicly demonstrated the daguerreotype in 1839, mechanically fixing an image from nature onto a metal support by the use of a camera. Simultaneously in England, William Henry Fox Talbot accomplished the same with the calotype, which fixed the image onto paper coated with silver iodide. In turn, the photograph fueled Realism. While Realist artists rarely worked from photographs (some did), the photograph's biggest conceptual strength was its claim to veracity. If the right to rule had traditionally been supported by art that idealized the powerful, the photograph suggested the possibility to literally show rulers' real flaws. In the midst of a revolutionary century, Realist painters sought to adapt photography's truth value to their art.

Another major influence on Realism was the explosion of socially critical journalism and caricature at the beginning of the July Monarchy (1830-48). Though the authoritarian reign of Louis Phillippe I would end in overthrow, the first five years of his rule allowed greater freedom of the press. It was in this moment that Honoré Daumier began publishing caricatures critical of the monarchy, such as the lithograph Gargantua (1831), in which he mockingly depicted the king as the gluttonous giant of François Rabelais's 1534 novel.

Engraving, which could be reproduced and disseminated in the press, enabled Daumier to circulate his critical compositions. Despite being imprisoned for six months for his negative depiction of the king as Gargantua, he continued to create the Realist lithograph Rue Transnonain, le 15 Avril 1834 (1834), which showed the brutal aftermath of a massacre of working-class innocents by the French government. The work was considered so powerful and dangerous to the monarchy that Louis-Philippe sent men to purchase as many copies as possible to be destroyed. Daumier would continue painting and engraving for several decades, producing socially focused works such as Third-Class Carriage (1862-64).

When the July Monarchy came crashing down in France in 1848, ushering in the Second Republic (1848-51), it was as part of a larger wave of European revolution that brought wide-ranging social changes in Germany, Italy, the Austrian Empire, the Netherlands, and Poland. These events, combined with the publication of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's The Philosophy of Poverty in 1846 and Marx and Engels's Communist Manifesto in 1848, cast a new light on the margins of society, and Realism became the visual language for their representation.

A friend of Proudhon and Realism's main proponent, Gustave Courbet led a multifaceted assault on French political power, bourgeois social mores, and the art institution. His exhibition of A Burial at Ornans (1849-50) at the Salon of 1850-51 marked the debut of Realism as a significant force in the European art scene, causing a scandal with its matter-of-fact depiction of a rural funeral on a scale traditionally reserved for allegory and history painting. The Stone Breakers (1849-50), exhibited in the same year, represented two anonymous, lower-class workers participating in poorly compensated, backbreaking labor, a scene that carried uncomfortable associations with Socialism for the Salon's middle-class audience. Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine (Summer) (1856) caused a similar sensation at the Salon of 1857 with a frank depiction of two prostitutes lazily reclining on a riverbank with their garments in disarray that offended bourgeois taste.

If in the 1850s Courbet painted large works with subject matter that questioned the values of French society, Édouard Manet pushed Realism even further in the 1860s. Having made a name for himself at the Salon of 1861 with his exhibition of The Spanish Singer (1860), he submitted Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863) to the Salon of 1863. Though the painting was rejected, it was shown in the Salon des Refusés ("Exhibition of Rejects"). There, Manet's frank depiction of two young dandies dining in a forest with a fully nude woman offended the sensibilities of its salon-going audience, especially middle-class men who participated in exactly those sorts of dalliances with Parisian prostitutes and who did not like to be reminded of this when out at art exhibitions, potentially with their families. Manet built upon and fed into all of these scandalous charges when he submitted Olympia (1863) to the Salon of 1865. Olympia, which places the viewer in the position of a bordello visitor attempting to procure a disinterested prostitute, made Manet's intervention even more obvious.

The critics, however, were playing directly into Courbet's and Manet's hands: the notoriety they commanded from their works was intentional, turning them into celebrities within the art world. Beside muddying the traditional categories and subjects of academic painting, Courbet, and Manet in his turn, would challenge the state art institution itself. When three of his fourteen submissions to the Exposition Universelle of 1855 were rejected for size considerations, Courbet rented space adjacent to the Exposition to construct his own Pavilion of Realism, in which he housed forty of his own works for free public view. When Manet was excluded from the Exposition Universelle of 1867, he too exhibited independently. Beyond drawing attention away from government exhibitions and creating publicity for their work, Courbet's and Manet's interventions emboldened future artists (most notably the Impressionists of the following generation) to exhibit their art independently.

While the Realist painters' manipulation of controversy through their subject matter is an obvious manifestation of their anti-authoritarian goals, their technical innovations may be less obvious to eyes conditioned by 150 years of modern art. At the time, however, the artistic distance between a canvas by Courbet and a traditional history painting were obvious and confrontational.

When Courbet debuted The Stone Breakers, critics accused him of purposeful ugliness and complained of the "flatness" of his composition, which was enhanced by the bold outlines surrounding his two key figures. A year later, his painting Young Ladies of the Village (1851-52) was attacked as clumsy, lacking in correct perspective, and disregarding scale in its portrayal of a trio of women who dwarf the cattle that stand near them. Eleven years later, Manet's painting Le déjeuner sur l'herbe was attacked on nearly the same grounds, with critics commenting negatively on Manet's coarseness of paint handling, the flatness of his composition, and the stark, contoured whiteness of his female figure. When critics correctly connected Manet's composition of the three-person figural group to High Renaissance works by Marcantonio Raimondi and Giorgione, their outrage heightened at his indecorous treatment of the Old Masters.

The follow-up exhibition of Olympia (coarser, flatter, more starkly contoured, and based on Titian's Venus of Urbino (1538)) proved that these manipulations to traditional academic painting were not the mistakes of a young, clumsy artist. Unwittingly, the critics had stumbled onto what would become the groundbreaking visual achievement of Realism: Courbet and Manet each made an artistic choice to move away from the Renaissance conception of a canvas as a "window onto the world" toward a flatness that revealed the canvas as a two-dimensional support to be creatively covered with pigment. This first step away from painting as a mere representational format was a crucible for generations of modern artists and a major reason for the continued popularity of Realism today. While Courbet was outspoken in his conviction that art could never be wholly abstract, his and Manet's nontraditional painting empowered future artists to move further away from the direct pursuit of naturalism.

Despite Courbet's insistence that socialism informed his Realist painting, not every Realist artist pursued his political goals. They did, however, share an interest in the life of the lower class and desire to represent it in high art. Jean-François Millet completed a trio of works, The Sower (1850), The Gleaners (1857), and The Angelus (1857-59), that represented the hard work of the rural peasant class with dignity, but with a less confrontational air than Courbet's canvases. The female painter Rosa Bonheur, whose progressive-minded parents allowed her to study animal anatomy in barns and slaughterhouses at a young age (while dressed as a boy!), first achieved fame for Plowing in the Nivernais (1848), a government-commissioned painting that depicts four farmhands driving steer to plow a field. As it was thought to reference a scene from George Sand's La Mare au Diable, this early example of Realism was spared the criticism cast on Courbet's large works. The Horse Fair (1852-55) further demonstrated her focus on blue-collar work and her ability to create dynamic compositions through close observation.

However, even Millet's seemingly innocuous celebration of France's rural backbone was received as potentially dangerous socialist content by conservative critics in the wake of the 1848 Revolution, which granted greater rights to provincial men. Jules Breton's paintings were considered a safer alternative, and has been referred to as "popular Realism." Breton's The Gleaners (1854) depicts the same practice as Millet's painting, wherein poor rural women are allowed to pick up bits of grain left behind after the harvest. However, Breton imagined the scene as one happening within a strict order: despite gleaning being "women's work," a man with a dog dominates the scene, overseeing the fieldwork. A steeple on the horizon would have communicated both the pious nature and Christian values of the peasantry as well as another form of governance to Parisians concerned about the growing equality they shared with their rural counterparts.

Though Realism was first a French phenomenon, it obtained adherents across Europe and in the United States. The American James Abbott McNeill Whistler befriended Courbet in the 1860s and painted in a Realist style. Yet Whistler was an advocate for "art for art's sake" and rejected the idea of painting as a moral or social enterprise a la Courbet. Nonetheless, his Symphony in White, no. 1: the White Girl caused controversy at the same Salon of 1863 where Manet courted scandal, because critics argued that it contained connotations of a bride's lost innocence.

Thomas Eakins became the United States' most prominent Realist painter, integrating photographic study into his works and revealing the character of his subjects through close observation. The Gross Clinic (1875), a portrait of the doctor Samuel Gross performing invasive surgery in an operating theater is rendered in unflinching detail. His choice of a contemporary subject (modern surgery) follows the Realist belief that an artist must be of his own time.

The German Realist Wilhelm Leibl met Courbet and saw his work when the French painter visited Germany in 1869. Recognizing his abilities, Courbet lured him back to Paris, where Leibl achieved considerable success, also meeting Manet before returning to Munich to establish himself as his country's premier Realist painter. He is best known for his images of peasant scenes such as Three Women in Church (1881), which brought the frank naturalism of the Dutch and German Old Masters into the modern era. Though the somewhat dated outfits that the three women wear indicate their low economic status (the new trends of the city have passed them by), Leibl ennobles them in their patience and humility.

The Realist Ilya Repin was the most prominent painter of his country in the 19 th century, responsible for bringing Russian visual art to the attention of European audiences. His large canvas Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870-73) celebrated the strength of Russia's lowest-ranking physical laborers. The novelist Leo Tolstoy would write of Repin that he depicted "the life of the people much better than any other Russian artist." Having traveled to Paris and become aware of the nascent movement of Impressionism, Repin chose to continue painting in a Realist vein, because he felt that Impressionist painting lacked the social motivations necessary to modern art.

The Realist painting movement ran parallel to the Realist movement in literature, exemplified in the work of writers like Honore de Balzac, Champfleury, and Emile Zola. Realist authors recognized in the artistic movement the shared desire to divorce from tradition and celebrated it, contributing to its success. Balzac's witty and incisive representation of society in the early-19 th century contrasted with the emotional grandeur of his Romantic counterparts much as Courbet's painting would in the visual arts.

Champfleury promoted Courbet's work as early as 1848, continuing to do so for decades, and Courbet painted him among his supporters in the 1855 masterwork The Painter's Studio (1854-55). Of Courbet's Pavilion of Realism, Champfleury wrote: "It is an incredibly audacious act, it is the subversion of all institutions associated with the jury, it is a direct appeal to the public, some are saying it is freedom."

Zola was one of Manet's earliest and most devoted defenders, recognizing his importance to modern art and declaring him a master of the future. By 1868, Zola could write: "I don't need to plead for modern subjects here. This cause was won a long time ago. After those remarkable works by Manet and Courbet, no one would dare now say that the present day is unworthy of being painted."

There was no defined "group" in Realism, as we might conceive of the later Impressionists as a coherent group who exhibited together: the Realist movement comprised of a number of artists working independently among similar lines. Though they knew each other, and the artists and writers were mutually supportive friends, there was no "breakup" or dissolution of the group. Thus, the historical and artistic motives that led to Realism's genesis and development continued in the art and ethos of painters across the globe for generations to come.

As the enfants terribles of the 19 th -century art world, Courbet and Manet are often invoked as the first avant-garde artists, and their mixture of art and critique laid groundwork for every socially engaged artist in their wake. Moreover, their visual trajectory into flatness had widespread ramifications for painting without which Manet's next step into Impressionism could not have happened. Their use of contour lines to structure form and separate it into panes of color were also an inspiration to the Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne and his followers, as well as the Cubists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

Even artists with drastically different goals than Realism named their debt to the movement. Giorgio de Chirico, the head of the Metaphysical Painting movement, wrote about his reverence for Courbet, who he acknowledged as an artistic father figure. Surrealism founder André Breton would celebrate Courbet's mixing of the artistic with the political; Surrealist dissident Georges Bataille named Manet the father of modern art for being the first to "destroy" the subject of painting, in Olympia.

The Ashcan School of the late-19 th and early-20 th century in the U.S. derived from the sometimes gritty, matter-of-fact depiction of city life was partially based on the figurative language and social awareness of Realism. Similarly, Social Realism, less an art movement than a cultural phenomenon, took Realism's relation to social justice as a given and made figurative works to combat the abstract art in vogue in the early part of the century. The Mexican muralists, American art workers in Depression-era New Deal programs, and French and German painters in the years leading up to World War II worked in this mode to create straightforward, legible works to transmit messages to their audiences. Social Realism should not be confused with Socialist Realism, decreed by Joseph Stalin as the state art of the Soviet Union in 1934. Though both shared a commitment to the education and edification of a lower-class, uneducated populace, the Soviet variant - a visual mélange of Repin's Realism and a sunnier Impressionism - became an official, academic art, supporting the regime and remaining largely unchanged until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

In Weimar Germany (1918-33), the artists of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) took lessons from the matter-of-factness of Leibl's Realist canvases to move beyond the distortions and abstraction of German Expressionism. Photorealism in the 1960s was born of a similar relationship to Abstract Expressionism, and though its artists did not always share the social motivations of Realism (preferring to link themselves to the example of contemporary Pop art, also a figurative language), their debt to the movement is visually apparent.